There Are No Rules in ASLAN WORLD

Meet the chronically online, LA-based designer who crafts irreverent ballet flats, XL furry boots and “hot clothes 4 hot boys.”

In a world where fashion often feels over-filtered and overthought, ASLAN WORLD emerges as a brand deeply rooted in reality. With an emphasis in feeling over formula, the label is led by CJ Aslan whose work is shaped by emotional awareness, artistic rebellion and a deep curiosity about how intangible ideas—like confidence, nostalgia and longing—can take physical form.

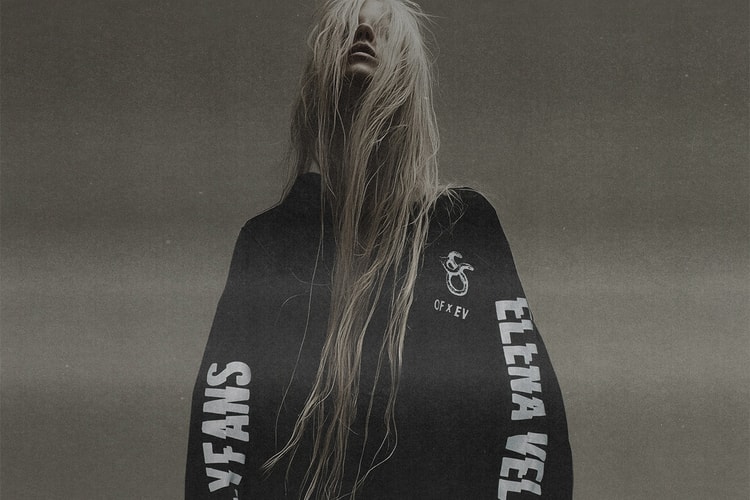

ASLAN WORLD‘s Fall/Winter 2025 collection, “BURNING RUBBER, OPEN HEART,” underscores her commitment to shattering labels with new iterations of her signature, spiked ballet flat and a garment line oozing in aughts sentimentality. From unretouched look books to footwear made with intentionally ripped tights, her approach challenges norms —not for the sake of disruption, but to make space for something more honest.

For this installment of Baes With Kicks, we speak to the LA-based designer about breaking out of categories in footwear design, her love of online aesthetics and why her new physical space feels more like a sanctuary than a showroom.

Continue reading for the full conversation and before you go, check out the brand’s new Aslan Teeth Flats, now available in “BLEACH” and “PEWTER” colorways.

Name: CJ Aslan

Location: Los Angeles, California

Occupation: Creative Director and Founder, ASLAN WORLD

You mentioned being inspired by feelings. How are you feeling right now?

I’m feeling everything. Our FW25 collection focuses on being hyper-aware and intuitive about feelings without holding on too tightly or expecting too much in return. That’s definitely how I’ve been feeling—very observant and trying to pay attention to how I feel without taking it too personally. I wanted to create more wearable pieces to complement our extreme designs. That concept led me to question how to make a feeling or a word wearable. It became about translating those broader, nuanced ideas into something tangible.

How did you start designing footwear and accessories?

I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I have a BFA, but I focused on a mix of installation, design, sculpture and fashion classes. I took a shape and theory course developed by the artist Nick Cave who explores the crossover between garments and sculpture. I never took a formal shoe-making class or a comprehensive sewing course. So, not knowing the traditional methods meant I never felt constrained by any expectations or rules. Had I taken formal shoe-making classes, I probably wouldn’t have created the types of shoes I design now or drawn inspiration from the unconventional sources I do. Without the pressure to adhere to traditional standards, I was free to explore, question and ultimately create without limits.

Why was now the time to launch an IRL space and what were the most surprising elements of bringing it to life?

Having a physical space that doesn’t exist solely for the making process is really interesting. It feels like a sanctuary. Everything from the lighting to the sound became just as intentional as how a zipper lays or the stitching color of a garment. The space holds the same weight as the pieces inside of it, coexisting together. It’s been so nice to bring people here and invite them to step inside the context of an item of clothing. It’s like a housewarming party that lasts forever.

Your campaign imagery oozes with feelings of being chronically online. Where does that inspiration come from and how does it show up in your creative process?

For me, the process has become so much more important than the final piece. There’s too much pressure to create hyper-finalized work. When it comes to hyper-online content, the actual product doesn’t matter as much as how it’s presented. People are often more intrigued by the fantasy of the unknown. You don’t have to force a high-definition, hyper-polished narrative. For my last look book, I shot it myself, and it’s not retouched at all. My connection to [the online world] comes from my first interactions with fashion and building my own visual identity. My online persona, moodboards on my computer, Tumblr and the concept of a “dream boy” or “dream girl” were all part of that. That’s where I first asked myself: “What do I want to wear?” and “Who do I want to be?”

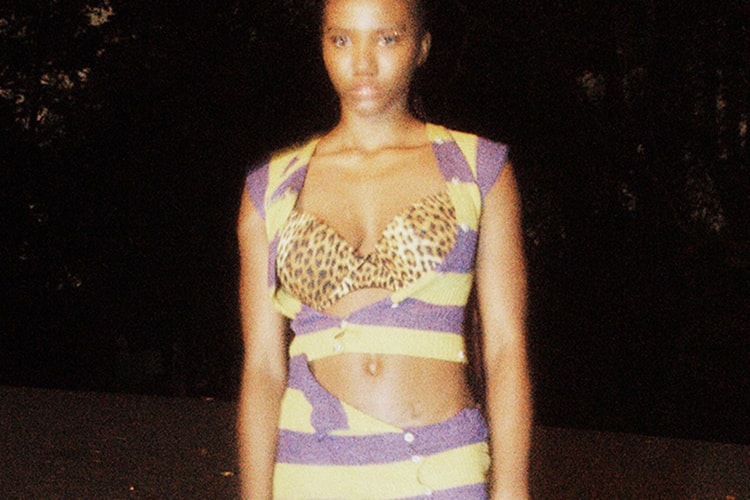

Speaking of dream boys, you say ASLAN WORLD is “Hot clothes 4 hot boys.” What gap did you feel was missing in the menswear market when you started the brand and how do you fill it?

With menswear and fashion, it often falls into two extremes. It’s either hyper-masculine or exactly what you would expect. On the other hand, if there are any feminine aspects, they tend to be exaggerated into a forced hyper-femininity. These categorizations don’t need to exist at all. No one is entirely one thing or another. Categorizations create a pressure for brands to cater to what they think their audience wants, but sometimes it’s simpler than that. Think about the original Justin Bieber hair flip. Every middle school boy copied that style because it was effective. It was simple, but it had a massive influence.

For me, creating something people like often comes down to three elements: nostalgia, a new idea and familiarity. Nostalgia evokes emotion, the new idea engages curiosity and familiarity makes it accessible. What makes something or someone attractive often isn’t the traditional definition of beauty. Confidence, ease and not trying too hard are always attractive. The hottest person in the room isn’t necessarily the most conventionally attractive, it’s the person who carries themselves with genuine confidence.

Why were you drawn to footwear and accessories as your first mediums for the brand?

I love texture, design, object-based concepts, architecture and furniture design. The elements of our shoes often come from those influences, which inspire many of our footwear ideas. We frequently use unconventional materials in our shoes. My factory loves that I consistently bring materials they claim are impossible to work with.

With clothing, there are more limitations because it involves considerations like fit, target audience and sizing. Accessories and shoes break boundaries. Shoes are eccentric objects on their own. They are often uncomfortable, impractical and seemingly nonsensical, but that’s what makes them exciting. You might wrap bandages on your shoes or find ways to numb your feet to wear the heels that you want. Humans have always done this unapologetically.

Do you have an example of a shoe material that you brought to the factory that shocked them?

Our shoes are mostly made of lamb, especially the ballet flats. Some of the newer ones are made from cowhide, but lamb is really thin. We have these new white lamb shoes with nylon tights sewn onto the pattern. The tights are intentionally ripped, so it looks like you’re wearing torn tights over your shoes. The manufacturers questioned why I wanted to put something that was already ripped on a shoe and sell it. But, the point is that they will continue to deteriorate.

Spikes are also a challenge because you have to distribute them evenly with different shoes sizes while maintaining the same visual effect. Ultimately, I love the idea of creating something that follows the same rules as a piece of art rather than a typical clothing item.

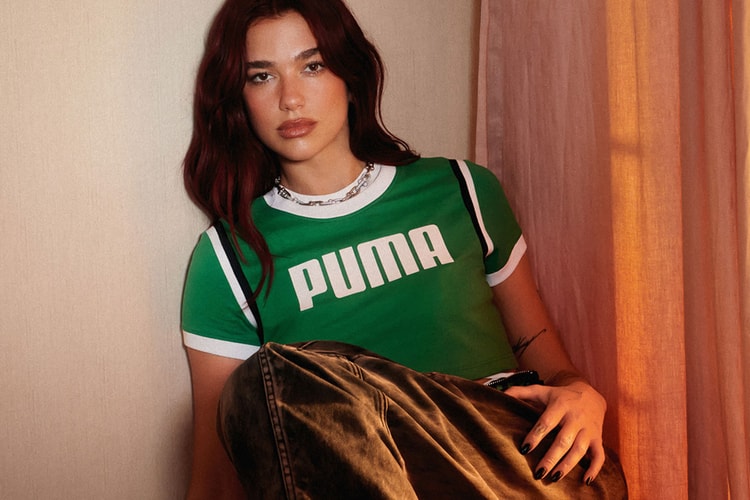

What’s your dream collaboration?

I’ve always wanted to do a checkerboard Vans design. I’ve dreamed of working with all those basic, classic silhouettes that have a lot of utility. I love the idea of not needing to reinvent something entirely but instead, reintroducing it. I’d love to put our brand name on a classic black-and-white checkered Vans but make it look super worn.

Do trends influence your footwear designs or do you try to stay laser focused on your own vision?

Initially, I wanted to release something no one had ever seen before. But then, [I realized] that if something is too nuanced, people struggle to access it. Trying to work with and respond to what works is the best thing you can do. If people are into it, there’s no need to keep making a completely new product. Right now, for example, we have seven colorways of our ballet flat, some without spikes and all of them have a matching bag in every material. That’s the game—being hyper-aware of what people respond to while staying true to your design process. Keeping that signature in mind and understanding why people were drawn to your work in the first place is the most important part.

Also, nothing is completely original; everything has been done in some form. What matters is how you present it, what you pair it with and what aspects you choose to exaggerate or emphasize. It’s not about copying existing ideas but recognizing that we are all subconsciously influenced by what we’ve seen before. The belief that you need to constantly create groundbreaking, never-before-seen concepts is more relevant in the fine art world. Fashion requires a direct response to what people want.