For the LGBTQ Community, the Coronavirus Pandemic Compounds Pre-Existing Hardships

As touchstones of solidarity and support become more difficult to access.

Though the global coronavirus pandemic is far from reaching a resolution, our current situation has made one thing strikingly clear: the need for social connection becomes even more pronounced in times of crisis. While in quarantine, we find comfort in shared experiences — cheering on healthcare workers at a set time each evening, participating in viral TikTok challenges, playing the same video games.

For the LGBTQ community, the pressing need for these shared rituals and points of connection existed long before the spread of COVID-19. Community gatherings provide relief from intolerant families, discriminatory workplaces and exclusionary overarching infrastructure. Now, the novel coronavirus and its frighteningly simple mode of infection — through the air we breathe — has forced community members apart.

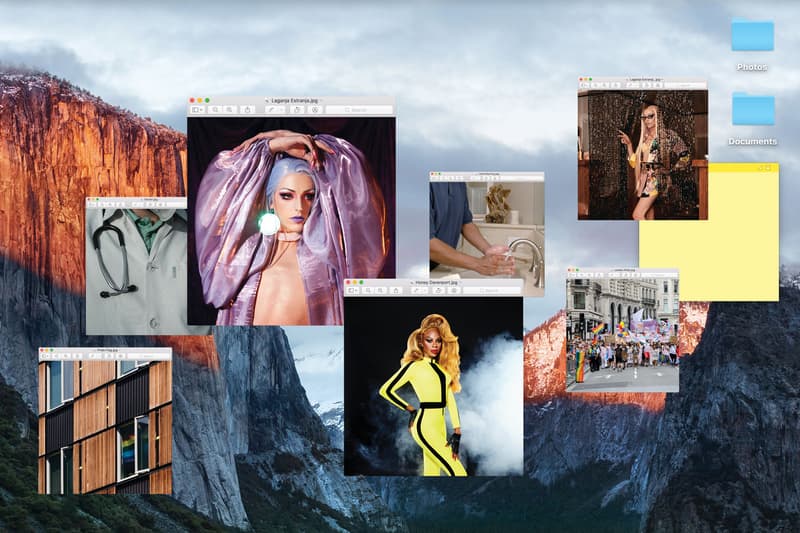

Though some have billed COVID-19 an “equal-opportunity” virus, that sentiment proves resolutely false. As with any hardship, the marginalized and disenfranchised are hit disproportionately harder than those with the privilege of being heterosexual and white, for example. As the virus temporarily shutters gay health centers, cancels queer gatherings and postpones Pride Month celebrations, the LGBTQ community faces a unique set of challenges in the midst of the current health crisis. HYPEBAE spoke with those working to unite and serve the LGBTQ community, from drag queen Laganja Estranja to Andrew Goodman of the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, about the hardships — and silver linings — the pandemic poses.

Queer performers face substantial financial losses.

As is the case with musicians, comedians and actors, drag queens have had to cancel or postpone live shows, leading to substantial financial losses. For Laganja Estranja, who rose to fame on season six of Rupaul’s Drag Race for her choreography skills and over-the-top catchphrases, live performances account for 90 percent of her income. Honey Davenport, a competitor on the eleventh season of Drag Race, estimates about the same. “I make very, very little — maybe 5 percent — off of my digital sales and merchandise,” she says.

Both Laganja and Honey are working around the limitations of the pandemic through digital drag shows, allowing fans to leave tips through apps such Venmo, PayPal and CashApp. “Whatever you got mama, I got it,” Laganja jokes. The Dallas-raised performer finds that her work schedule changes on a day-to-day basis. Besides hosting daily Instagram live sessions, Laganja also appears on a weekly Twitch stream, hosted by fellow drag queen Biqtch Puddin’, and recently promoted a digital release party for Dua Lipa. Honey works with a similar strategy. In addition to receiving tips on online performances, she also allows her fans to pay for a subscription to a weekly lineup of performances that she uploads to Dragforfans, a relatively new platform that operates as a drag-specific version of OnlyFans.

Though Laganja cites losing $10,000 USD in one month due to canceled performances, she’s been “completely overwhelmed” by her fans’ generous digital tipping. “Those dollars add up and it only goes to show how strong the LGBT community is,” she praises. Still, the loss of community bonding over live performances and other queer events — such gay club and bar-hosted viewing parties of Rupaul’s Drag Race, currently airing its 12th season — is distinctly felt. “I always joke that it’s gay church, because it gives us a reason to all get together and unite over one thing,” Laganja says of weekly Drag Race parties. “A lot of gay people need these safe spaces, these places to be able to go and express themselves to the fullest,” she adds. “We’re going to continue to find ways to survive this, but it’s still obviously never going to be the same energy and type of connection you’re able to have in-person or one-on-one.”

Honey also touches on the need for queer content during the pandemic. “Friends who used to come out and celebrate at my shows with me still need to escape,” she says. Though she acknowledges her digital shows as a means to put food on her table, she also describes them as a “social responsibility.” “I’ve been given a gift to create things that give people peace and joy and happiness. I should be doing that while sitting in the house, just like I would if I could walk around,” she explains.

Touchstones of connection go virtual, posing limits.

Besides the temporary pause on drag performances and parties, modes of connection such as gay youth groups and LGBTQ-friendly therapy are now taking place through video conferencing apps such as Zoom and Google Hangouts. From the Bradbury-Sullivan Center‘s virtual book discussions, digital support groups from the Brooklyn Community Pride Center and online performances from New York‘s Youth Pride Chorus, LGBTQ community centers around the country are finding alternatives to in-person programming such as interest groups, social hours and workshops.

That being said, digital events are only accessible to those with a computer and Wi-Fi at home, affordances that LGBTQ folks — who, according to Andrew Goodman, associate director of medicine at the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, “face higher rates of unemployment including stigma and discrimination, and thus higher rates of poverty” — may not have the income for. In addition, those quarantined with unsupportive family members may not feel comfortable, or may even be altogether forbidden, from accessing queer support online. “Not being able to physically remove yourself from that kind of environment can be a real challenge,” Jeff Klein, chief operating officer of The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center, posits.

Further, the Los Angeles LGBT Center reports that the disturbing trend of “Zoombombing,” in which hackers hijack a video call with slurs and graphic imagery, has been directed at LGBTQ-specific meetings. “[Zoombombing] can be traumatizing for the people who are participating and need a safe space to share their thoughts and feelings,” Tanya Tassi of the center’s policy department says. In response to these targeting hijackings, the Los Angeles-based organization offers an online forum on how to protect Zoom calls from unwanted visitors.

“Our communities…often rely on support systems other than traditional family models,” Goodman adds. With this in mind, support and connection become even more important to the health and growth of the gay community. Though LGBTQ centers are doing the best they can to provide virtual alternatives to face-to-face therapy and other resources, they may not be adequate replacements for some.

Healthcare inequities threaten sick members of the gay community.

“This is not our first time facing a virus,” Laganja says, a sober reminder of a fact that has spurred countless think pieces comparing and contrasting COVID-19 with the HIV/AIDS epidemic that began in the early ’80s. Longstanding prejudices, including those borne out of misinformation regarding HIV and AIDS, have infiltrated the mainstream healthcare system and led to institutional discrimination against gay patients.

Klein confirms these prejudices have led to healthcare-related apprehension amongst the community. “We’re hearing that folks are anxious about their ability to access affirming healthcare during the pandemic. In particular, trans and gender non-conforming individuals are concerned about being discriminated against if they experience symptoms and want to seek testing for COVID-19,” he attests.

Klein’s observations are likely the result, at least in part, of governmental tolerance of homophobia. Just last month, White House Faith Adviser Ralph Drollinger wrote in a Bible study that the novel coronavirus is the “the consequential wrath of God” retaliating against those with “a proclivity toward lesbianism and homosexuality.

Madonna Cacciatore, executive director of LA Pride and the Christopher Street West Association, also adds that healthcare for the LGBTQ community tends not to be funded equally. “We’re less likely to have health insurance and more likely to be refused healthcare,” Cacciatore explains. “It’s important to remember that health inequities and disparities of care were prevalent for LGBTQ+ people before COVID-19 arrived. All of that hasn’t gone away because of the pandemic. If anything, it has put our community at greater risk.”

Support can still be found.

Despite the pressing consequences of the pandemic, Tassi notes that gay health clinics, including those located at the Los Angeles LGBT Center and the Resource Center in Dallas, are considered essential businesses and remain open. In addition, some centers continue to offer critical services without virtual alternatives such as HIV testing, meal deliveries for the elderly, distribution of canned goods and hygiene products to those without access and temporary shelter for displaced youth. ”Our community centers continue to give back amid the challenges, just like they always have,” Tassi says. “If you’re feeling isolated, reach out via phone to your local LGBT community center,” she adds, citing CenterLink, a directory of centers, as a resource for finding one nearby.

Goodman also points out that crisis, as tragic as its consequences are, forges stronger community bonds. “This pandemic — much like the AIDS crisis — has united so many of us in ways we couldn’t have imagined,” he observes. “We’re in this together. We’re collaborating with Housing Works to care for people who are homeless; we’re working with Gay Men’s Health Crisis. There is so much collaboration between [LGBTQ community organizations] and it’s beautiful to see.”

As for Pride Month, parades and events in cities including Los Angeles and London have been postponed. However, organizers are looking into virtual and digital alternatives to ensure that the community can still celebrate come June. “I am in constant contact with my colleagues in San Francisco, Boston, San Diego and other cities around the world, as well as the global InterPride organization,” Cacciatore says. “[The current situation] has caused us to come together in a trying time as we are all working to create the best version of Pride we can and ensure we all have a Pride to remember, no matter the situation.”

Being an ally begins with action.

“The word ally is a verb, which means it’s action-oriented,” Tassi says. Besides regular phone check-ins with gay friends and family members, she also recommends helping older folks who identify as LGBTQ with their grocery shopping and medication pick-ups. “LGBTQ+ seniors are particularly vulnerable, statistically, since they are more likely to live alone, face isolation and are less likely to have familial support,” Cacciatore attests.

Both Klein and Honey urge allies to get involved politically. “In the U.S., the patchwork of LGBTQ legal protections across different states means that some folks can still lose their job or housing due to their identity, or will have a much harder time accessing healthcare they need,” Klein explains. “Take this time to educate yourself on the state of LGBTQ rights where you live and take action accordingly.” This can mean calling local representatives, donating to organizations that are fighting for equality under the law, raising awareness via social media or volunteering help to your local LGBTQ community center.

“Our queer community, and especially our POC queer community, has already been at a social and financial disadvantage for a while,” Honey says, specifying that it’s crucial to talk to elected officials with queer people in mind. “When we’re listing off our demands, [make sure] we’re looking towards a future where our people are more accepted than we were in the past.”

Ultimately, the impulse to blame and “other-ize” marginalized communities during times of crisis hinders progress across the board. If we hope to effectively diminish the novel coronavirus, Goodman argues that history cannot repeat itself. “Fighting against LGBTQ discrimination was a key part of controlling HIV [in the 1980s],” he asserts. ” Similarly, we must resist any COVID-19-related discrimination today if we hope to bring this virus under control. We must all be vigilant about the ways that stigma impact the health and wellness of our communities.”

Resources for the LBGTQ Community

Affirmations

Alexis Arquette Family Foundation

Apicha Community Health Center

Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center

Brooklyn Community Pride Center

Callen-Lorde Community Health Center

CenterLink: The Community of LGBT Centers

Compass LGBTQ Center

Gay Men’s Health Crisis

LGBTQ National Help Center

Los Angeles LGBT Center

Nspire Outreach

Out Alliance

PFLAG

Pridelines

SAGE USA

The Ali Forney Center

The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center

The Okra Project

The Trevor Project Crisis Hotline

Trans Wellness Center

TransLatin@Coalition